Messy Guy

Do you really want to spend your life doing dishes?

Last year, when I had even less of an idea of what I was doing on this blog, the first subject I wrote about was about cleaning my espresso equipment. My words, from then:

“I hate coffee grounds. The bits of oil that come off the ground beans stick to every surface. After inheriting an espresso machine from my sister and brother-in-law, I have gone off the deep end: modding the grinder, ordering parts from Europe, and soliciting strange, fermented beans.. [t]he counter continues to collect coffee-dust. Last Sunday, I deep cleaned the entire set-up, the stench of isopropyl alcohol clinging to everything, microfiber towels freckled with debris.”

Now, ten months later, I have to admit a secret. You might think that writing about cleaning would inspire me to do it more, and maybe even create a habit, but the last time I deep-cleaned my coffee stuff coincided with the last time I wrote about it.

//

Being sloppy is a privilege, one that I have benefited from and felt shame for my entire life. In the house I grew up in, mother would say, without looking at me, in a serious-yet-gentle voice, don’t leave a trace, as she picked up some cup I left on a side table, two or three days after it was used. Echoing a sentiment protected outdoor areas use to dissuade their visitors from littering, don’t leave a trace became an anti-mantra that haunted me1. The phrase like a bell reverberated through my head constantly, and I would sometimes heed the call, but most oftentimes, I would ignore it, as sons are likely to do.

I remember the first time I lived away from home, in a house close to my college campus. With distance comes a gross clarity, exposing the degree to how unkempt I really was. Dishes left overnight in the sink? Guilty. Don’t leave a trace. A coffee mug balanced on a precarious ledge, set down after talking to a roommate about whatever we discussed? That’s me. Don’t leave a trace.

The messiness grew to its most egregious when a roommate2 and I stayed up all night, pumping music throughout the house (people were definitely sleeping) and being rambunctious to the point of opening a bag of brown rice and spilling its contents all over the living room floor. I still have a picture of the morning after; shadows caught on every grain, defining it; like ants sleeping atop everything. Don’t leave a trace.

I got my first credit card in 2015. My first job a year after that. Becoming a participant in our economy was being ushered into a rapidly evolving retail and online landscape that fought for my attention. They so desperately wanted me to want to buy things. Amazon’s quick ascension into providing anything and everything you “needed”, with convenient returns and two-day shipping, was unheard of. Every season, something new and exciting and loud popped until in the aisles of the local H&M or Zara, tempting us with novelty and constant reinvention. The rise of micro-transactions in phone apps created environments of free-to-play dopamine hits. Ticking clocks, hot deals. Being a consumer felt gamified and fun, not unlike a hobby.

Now, in 2025, consumerism has gotten insanely good at itself. It seems like every company on earth uses the same never-ending, hyper-aggressive, always-on methodology to steal our interest. With industries, like fast fashion, constructed around the mercurial nature of tastes, the fear of being kept out of what’s en vogue and what’s not creates an endless cycle of desire. There’s not only fashion week. There is the biyearly Apple developer conferences, announcing the new slimmer computer.

Part of how these behaviors stick is by distancing the consumer, us, from the impact of our collective waste and harm. It feels pushed out of our conscious-functioning mind and into our dark, gooey subconscious.

I know the ice caps are melting at an alarming rate. I know that, but it takes an effort to feel it. I have never seen the ice caps up close; I have never heard the sound of these glaciers cracking. It goes the same with a lot of other things. Smaller harvests and worse conditions for farm workers aren’t immediately conjured up when I buy corn in a can. Slaughterhouses are sadly reduced to statistics; natural disasters are footnotes until they blow away our front door.

//

The grinder is caked with months of coffee dust. Beans from around the world congeal and create a coating of neglect. It’s been weeks since I last pulled a shot of espresso or made a latte. With shame, I’ve spent my mornings button-mashing the Keurig to satiate my caffeine fix.

Enough is enough.

I take to the whole set-up — kettle, grinder, and machine — and begin cleaning again. Only this time, the act of cleaning felt necessary. It felt good to take cloth to chrome, to rinse out the brown-crusted drip tray. As the machine gets cleaner, I get excited by it. The more excited I feel, the deeper I go. I run a toothpick around the corner and crevices of the grinder. I begin to rearrange the whole set-up in imperfect fengshui. A mirror shine develops on the chrome. I see myself in it.

//

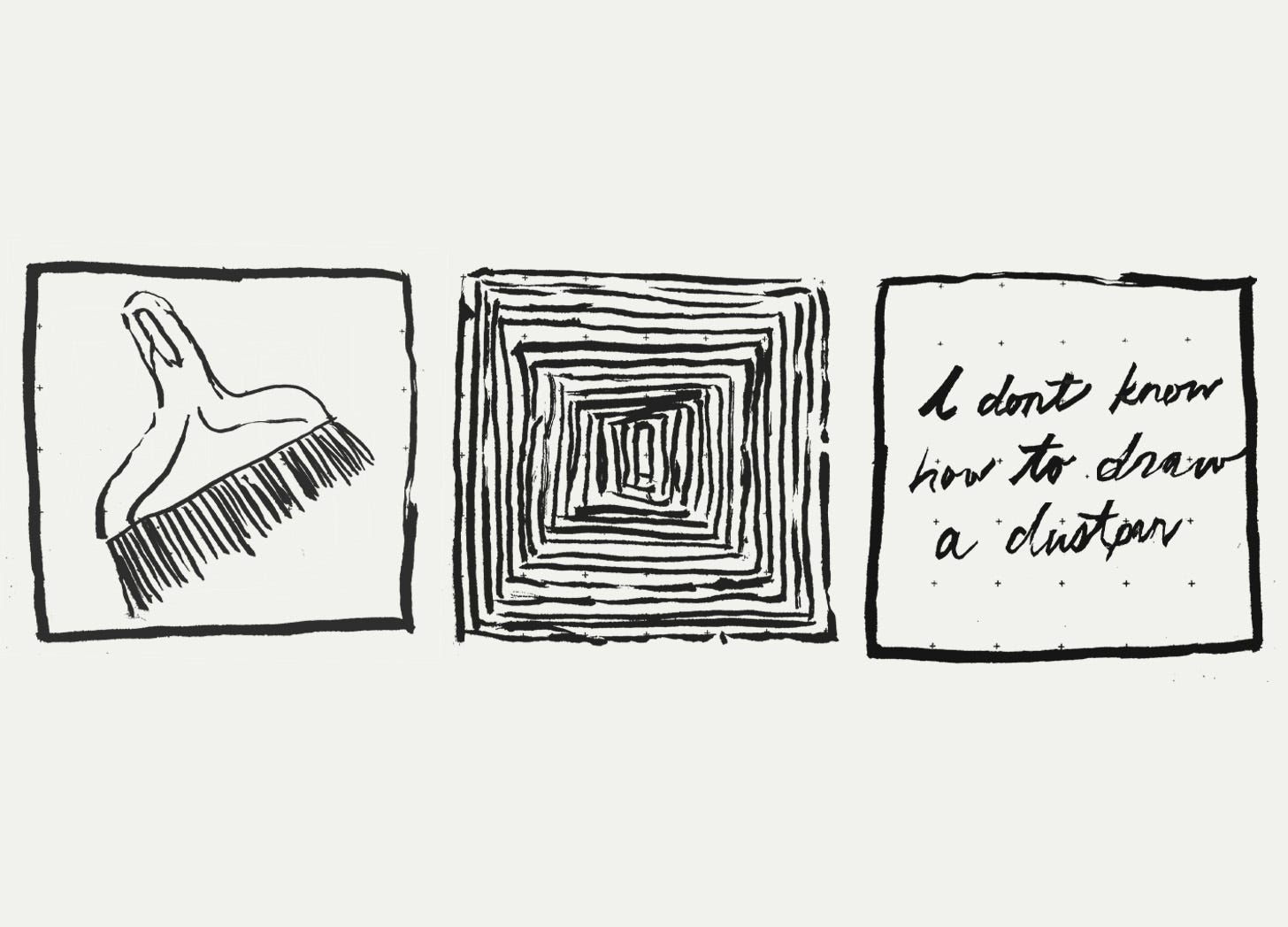

There is a word we hear from an early age used to describe a responsibility we don’t necessarily want. Chore. Chore lugs negativity around like an anchor. Chores are the worst! Chores suck! When I was younger, I detested chores. I didn’t understand why the bathroom needed to be cleaned if it was going to get dirty again. I didn’t understand why we needed to clean our nice, white ceramic plates when we could buy plastic ones at the store. Do you really want to spend your life doing dishes?

The problem with this perspective is a failure in connection. When I was younger, I wasn’t connected to what was around me. I didn’t see cleaning as my responsibility, so I didn’t see a reason to care. It’s going to get ruined anyway, so why bother? Why own nice things if they are destined to obsolesce? Futility is often a way out of responsibility. Chores then felt like some kind of obligation, or payment, for my existence. Chores beget futility and repetition and monotony.

That crucial choice between futility and its alternative is at the heart of privilege. Caring and choosing to care is a motor that drives the ship, and without it, the entire thing comes to a halt. Giving a shit, giving anything of yourself is immediately a way in — a connection point. I care because I touch it. I am a part of it, and I must be present for it. When I care for my products or my waste or my environment now, I feel padlocked into the context of those objects, wholly aware of my actions, wholly aware that I live in a world larger than myself.

Is it more work? Yes totally. Can it be perfect? No. Are individual actions hyper-emphasized when it is corporations whoare to be blamed for a larger majority of climate change’s problems? One hundred percent. However, the value generated from being a responsible item owner and a thoughtful consumer I believe is worth the effort. I feel connected to what I use. The things around me have greater meaning.

//

One of my pals Bryce owns and takes care of a 1993 Land Cruiser. He named the car Duke. Duke is a year older than Bryce. Parts of it decay, and mechanisms fail. Bryce is constantly making repairs, scouring online forums of other cruiser enthusiasts, looking for knowledge long lost to time. It is an object that has every right not to exist, Duke is kept alive by Bryce’s effort.

Sitting inside the cruiser itself feels deep. It doesn’t feel fragile. There is authorship to the care — key choices made when either respecting the original engineered machinery or upgrading to something more modern and comfortable. Duke glides on the freeway to take us out to the bowling alley. Duke traverses the sandy dunes of Baja California, the loose humus of forests near and far. It represents time and care, investment and design, intention and maintenance. I maintain that it is one of the most beautiful objects someone I know owns. It shouldn’t exist; it shouldn’t be beautiful; but it does and it is.

If I look away, the world falls into a black, inky darkness. If I look away, I don’t have to deal with it. Yet, things continue. Humans make an effort to mine the earth. Humans propose alternatives. Water erodes the canyon. A billionaire builds a casino on ancient land. I can choose not to look, but I want to engage with it. I can’t abandon the privilege to take care of what I have. I can’t abandon what little bit of the world I walk in because it’s a world I share with others.

The process is imperfect. There are still too many coats in my closet. When I get sad, the desire to buy more, to have more, burns hot like an ember. When this happens, I step back and take inventory of what I do have. I notice what needs repairing. I oil my cutting boards. I sharpen my knives. I learn how to take care of my own, twenty-year-old car. The shoes return to their boxes to keep their shape for just a moment longer.

A big thank you to Bryce Drobny for all our wonderful conversations about cars, movies, and putting intention into your work. He makes wonderful travelogues and maintenance/repair content on youtube and instagram under @la.cruiser! Also not mentioned by name, an acknowledgement is in place for my dear friend Elisha Knight, whose care for our breathing environment inspired this piece.

This was totally her intention; she affected the same tone each time she said and said it often she did. Mothers are very good at this.

Redacted, for love, because this next part is gross as hell.

Some truly wonderful words, sentences and thoughts here! I have had my own expresso machine cleaning moment more than a decade and several machines ago. It took tremendous focus and concentration but also provided great satisfaction and connection to the devices enhancing our existence. That said—with the astonishing increase in the price of these machines and the challenges of getting them repaired, we’ve abandoned the home machines for the perfect cup provided by a low tech pour through. Expresso becomes a larger world treat. Thank you Jonathan for sparking all kinds of considerations here. I look forward to more posts of your writing about anything!